Previous First Next

SALAMIS IN THE ISLAND OF CYPRUS.

BY ALEXANDER PALMA DI CESNOLÀ, F.S.A.,

page 25

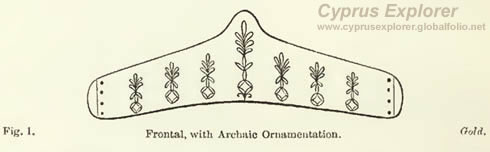

example. Among others, I found a frontal indented en repoussé, with lines marked in a pattern which illustrates the art-history and geographical situations of Cyprus, as it was alternately subjected to the influence of Egypt, Assyria, Phoenicia, Greece, or Rome. Lying, as the island does, on the highway between the East and West, at times an entrepôt, and occasionally impressed by the taste or education of more than one of these nations at the same time, it is not wonderful that relics which were found in Cyprus are of an extremely complex character in respect to the art they display, and that in not a few cases it is absolutely impossible to discriminate between these influences, and thus to decide without a doubt to which 1 Writing of his discoveries in that vast metropolis of the dead, Warka, in Lower Chaldea, Mr. Loftus, in his Ghaldea and Susiana, p. 211, stated, of the corpses ho exhumed with their slipper-shaped coffins: " Thin gold leaf sometimes appears to have covered the face like a veil; and one or two broad ribbons of gold not infrequently occur on each side of the head." " Gold liiminse, with archaic reliefs, were found in quasi Etruscan tombs at Monteroni."—See Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria, Dennis, 1878, i, 223, note. nationality they severally refer. This uncertainty affects our judgment, and often compels us to hesitate about the very age of certain relics, which we cannot with certainty attribute to one more than the other of the powers which have successively dominated in the island. Broadly speaking, however, I cannot be wrong in ascribing the greatest antiquity to the remains in which the older forms of Egyptian designs occur; the next, to that class which bears traces of Assyria; the third, to those in which we recognise the marks of Phoenicia. In the last case, however, there is this difficulty, that Phœnician designs, as such, can hardly be said to have existed independently and without any reference to Egypt on the one hand, and Assyria on the other. As might be expected, the art-works of Tyre and Sidon, which undoubtedly abound in my collections, are distinguishable from others by the presence of the combined influences of the eastern and southern neighbours of the greatest trading and manufacturing people of antiquity. In fact, where we find Egyptian modes corrupted by Assyrian admixture, or Assyrian modes affected by quasi Egyptian rendering, we recognise what is universally ascribed to Phœnician makers. The fourth order in antiquity among Cypriote remains comprises works which are very numerous, and, generally speaking, unusually beautiful, and emphasized by Greek taste, skill, and learning, in design. The fifth order is Roman,' which, strange to say, is hardly ever unaffected by that Greek spirit which thus proves to have been for ages domiciled as paramount in Cyprus. As to later orders than the Roman, it is not necessary for me to be concerned at present, beyond what may be required to enable me to state, that in the rich collection of coins which I have formed are specimens of Byzantine, or later Greek manufacture, of Gothic, Venetian, and even Renaissance origin. I have been led into this disquisition by means of the indented pattern on the gold relic which is here engraved (fig. l), and displays very distinctly the Egyptian influence on the Assyrian type of ornamentation. These remarks are applicable to the art-works of Cyprus of all kinds, not to golden instances alone. But the difficulty of discrimination, to which I have referred, is greatly increased by the existence of a numerous body of nondescript antiquities, especially terra-cottas, to which we are accustomed to ascribe a purely native origin, and cannot group them with either of the classes in question above. They are generally rude and uncouth, disproportioned, and without distinguishing style. They are represented by numerous instances in the Lawrence-Cesnola collection; in that which enriches the Metropolitan Museum at New York; Dr. Schliemann found the like on his "Trojan" hill, and was much exercised by tKeir peculiarities; they have been found in Greece; and in Etruria. As to the last-named place, the museum at Bologna, and other provincial collections in the north of Italy, are by

no means poor in respect to these quaint and rude, if not invariably primaeval relics. We must never forget that mere rudeness of execution does not absolutely affirm the extreme antiquity of any object.

Previous First Next

|